PRINCE GEORGE'S COUNTY, Md. — One Maryland County is known for having some of the wealthiest African-American communities in the nation, but history shows it has not always been a welcoming place for America’s black citizens.

In 2017, BET ranked five Prince George’s towns and cities among its list of top 10 most affluent African-American communities in America.

The report highlighted communities like Mitchellville where the median household income is $109,184 for a population that is 85 percent African-American.

"There's a lot of jobs being created from [the federal government] and a lot of those people move to the suburbs,” said Synatra Smith, the education curator at the Prince George's African American Museum and Cultural Center. “And, Prince George's County just happens to be right outside of DC."

But, Smith points out that early in the America’s history, Prince George’s County was one of the last places in Maryland that an African-American would want to visit.

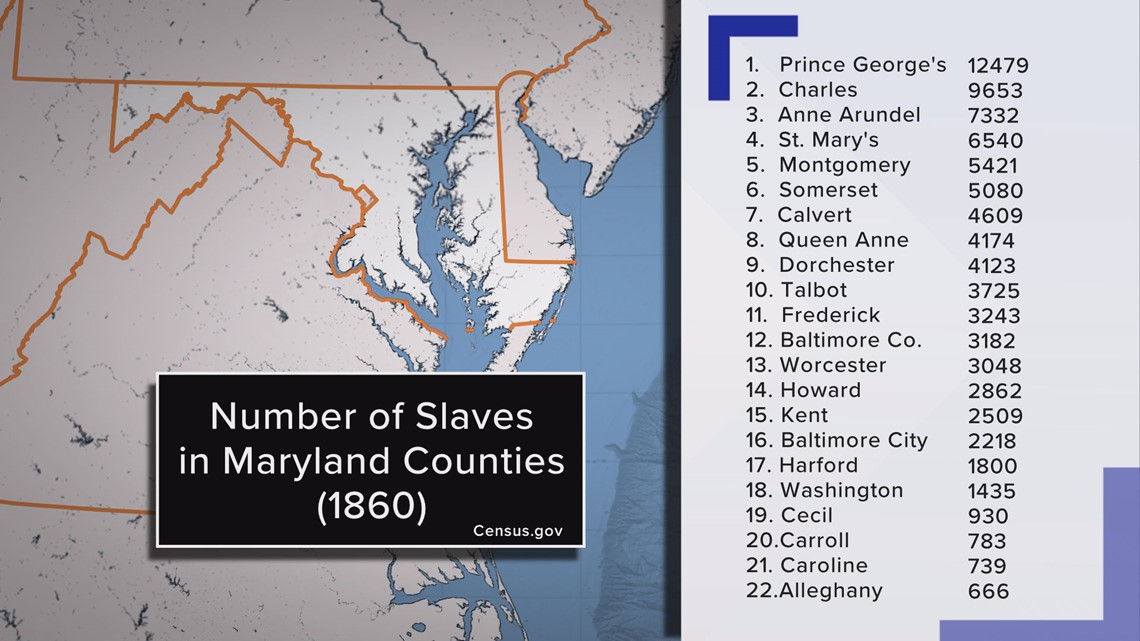

"No, definitely not,” she said. “The highest ratio of enslaved persons [in Maryland] was in Prince George's County up to abolition."

In 1860, there were more than 12,000 slaves in Prince George’s County. That number was more than the amount of white and free blacks combined residing in its borders.

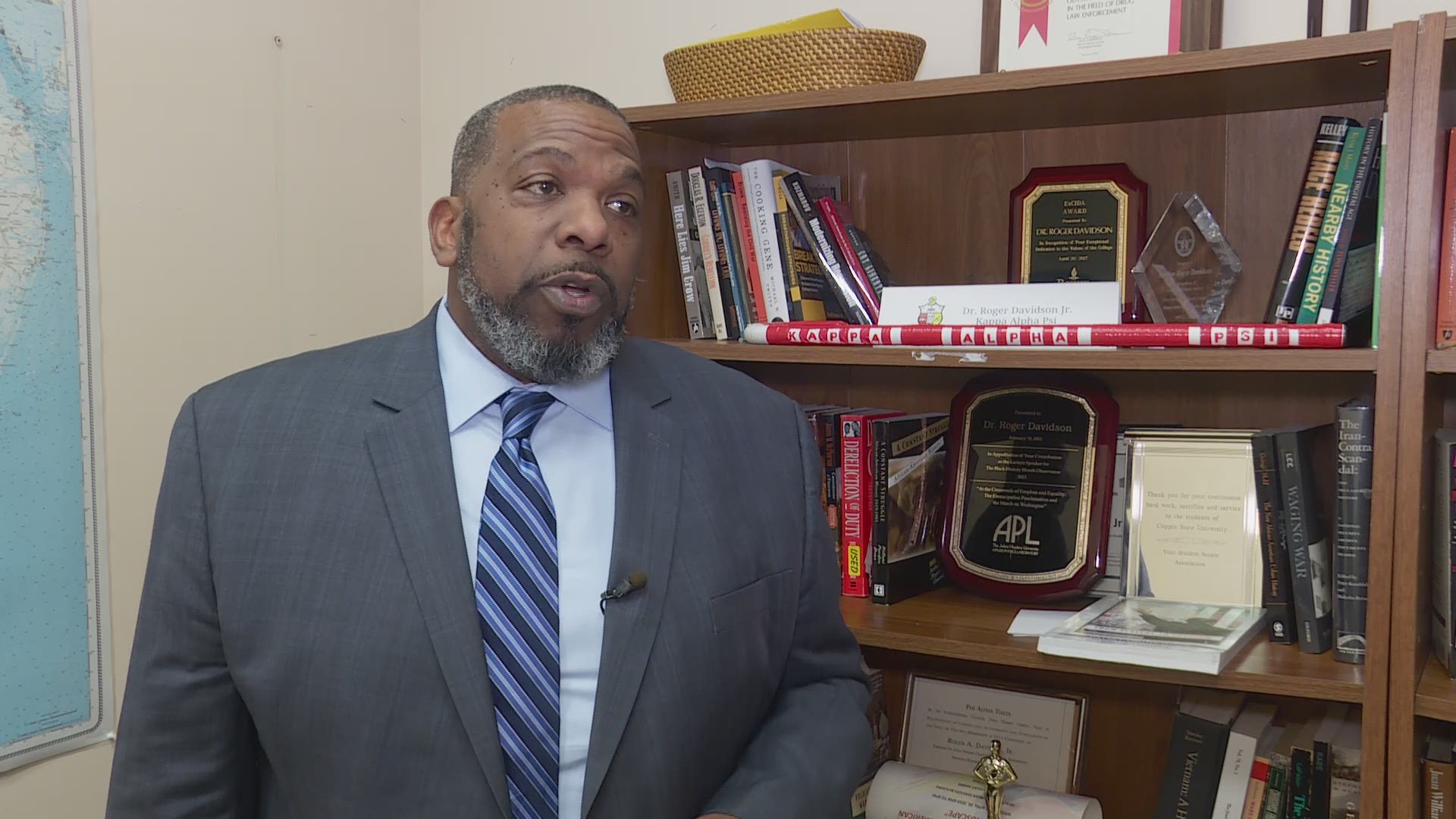

Dr. Roger Davidson, an associate professor of history at Bowie State University, said such statistics were not always common in the Mid-Atlantic.

“Per capita, it is somewhat rare,” he said. “It is somewhat rare."

The main cash crop in Prince George’s County, before the Civil War, was tobacco. Davidson said local property owners relied on large numbers of slaves to harvest the plant.

He added that was part of the reason why Prince George’s County had more slaves comparable to other communities in Western Maryland or near Baltimore.

“It's closer to the South,” he said. “Tobacco is king. It had been for a long time and they had maintained it."

In 1862, the District of Columbia abolished slavery. The act, brought forth by President Abraham Lincoln, inspired many blacks in Prince George’s County to head south into DC to acquire their freedom.

Bowie State History Professor Dr. Roger Davidson details the history of Prince George's County during the Civil War.

African-Americans who stayed in Prince George’s County would eventually have to deal with segregation in many facets of life.

This was apparent in the Prince George’s County communities of Brentwood and North Brentwood.

The towns sit next to one another, near the DC line, along Rhode Island Avenue.

North Brentwood was the earliest incorporated African-American community in Prince George’s County, according to the National Register of Historic Places. It was planned by Captain Wallace A. Bartlett, a veteran commander of US Colored Troops.

The segregated community was prone to flooding due to its proximity to the Northwest Branch of the Anacostia River.

Meanwhile, Smith said restrictive deed covenants prevented property owners from selling land to blacks in the drier community of Brentwood.

"If you're a black homeowner, or someone looking to purchase a home, there are going to be places that we were not allowed to purchase homes just because of the fact that we were African-American,” she said.

North Brentwood, and the communities around it, were also known locally as “sundown towns” or communities where blacks were known to be arrested by police if they were caught outside after dark.

Former North Brentwood Mayor Arthur Dock, 86, has lived in North Brentwood his entire life.

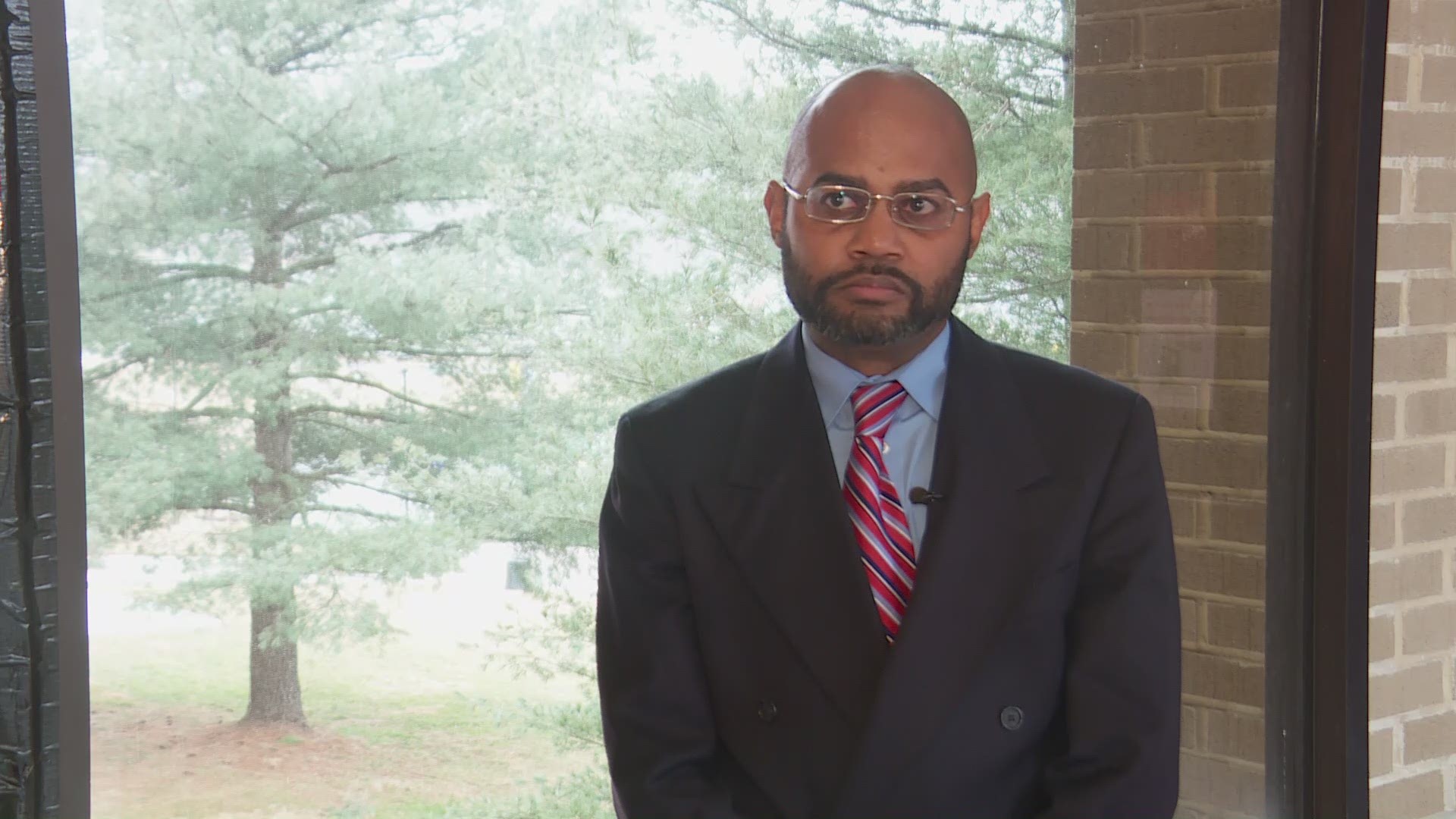

Bowie State University History Professor Dr. Tony Gass discusses Prince George's County history with segregation.

He said families in North Brentwood worked to support one another.

"There was so much love in the community and families worked together to provide a great experience in the town for their children,” he said.

However, he said he also remembered some of the area’s past segregationist acts.

“My brother, and their friends, set pins at the bowling alley in Mt. Rainier,” he said. “But, after that place closed, they had a certain time they had to leave the limits of Mt. Rainier. And, they all lived in North Brentwood."

African-Americans were also confronted by segregation in the classroom.

In 1954, the United States Supreme Court reached its landmark decision in Brown v. Board of Education, which effectively ruled segregation in public schools unconstitutional.

However, many Prince George’s African-Americans complained that segregation in schools was alive and well in that Maryland county years after the Supreme Court handed down its decision.

“Unfortunately, that is not an anomaly,” said Dr. Tony Gass, a Prince George’s County native and adjunct professor of history at Bowie State University. “That is not irregular. Some places in the United States, particularly the South, purposely dragged their feet."

The status quo was unacceptable to Prince George’s County NAACP President Sylvester Vaughns Sr.

Vaughns, and the NAACP, filed a lawsuit against the Prince George’s Board of Education on the behalf of his son, Sylvester Vaughns, Jr., that claimed segregation continued to be practiced in the school district in various forms.

"He took a lot of heat for that,” Vaughns Jr. said. “Phone calls to the house, letters to the house that threatened to kill him and burn him up. A lot of bad things."

Vaughns Sr. eventually won his suit.

A judge ordered the school board to execute a court-ordered desegregation plan, using busing, to bring an end to racial segregation in the school system.

Vaughns Jr. said he did not realize just how different things were for black and white students in Prince George’s County until he was transferred to a predominantly white school where the teachers had more experience.

Prince George’s County’s history when it comes to race may leave one confused as to how it would eventually become a place where African-Americans would seek out as a place to raise their families.

But, Gass said a few factors ultimately encouraged blacks to live in the community, like the large well-paying federal jobs in the District.

He added that the large number of universities in the area, like Bowie State, Howard University and the University of Maryland-College Park, also made Prince George’s County appealing to African-American black families.

“They're bringing a brain trust of people that are middle class, and upper-middle class, who want to reside in the area,” Gass said.

He said when you mix all of that in with the charm of the communities that make up Prince George’s County, you get a winning formula.

"Most people, I'm proud to say, once they come to DC, the DMV area, they don't want to leave," he said.