LEESBURG, Va. — Jim Koenig believes a higher purpose brought him to woods in Loudoun County, Virginia.

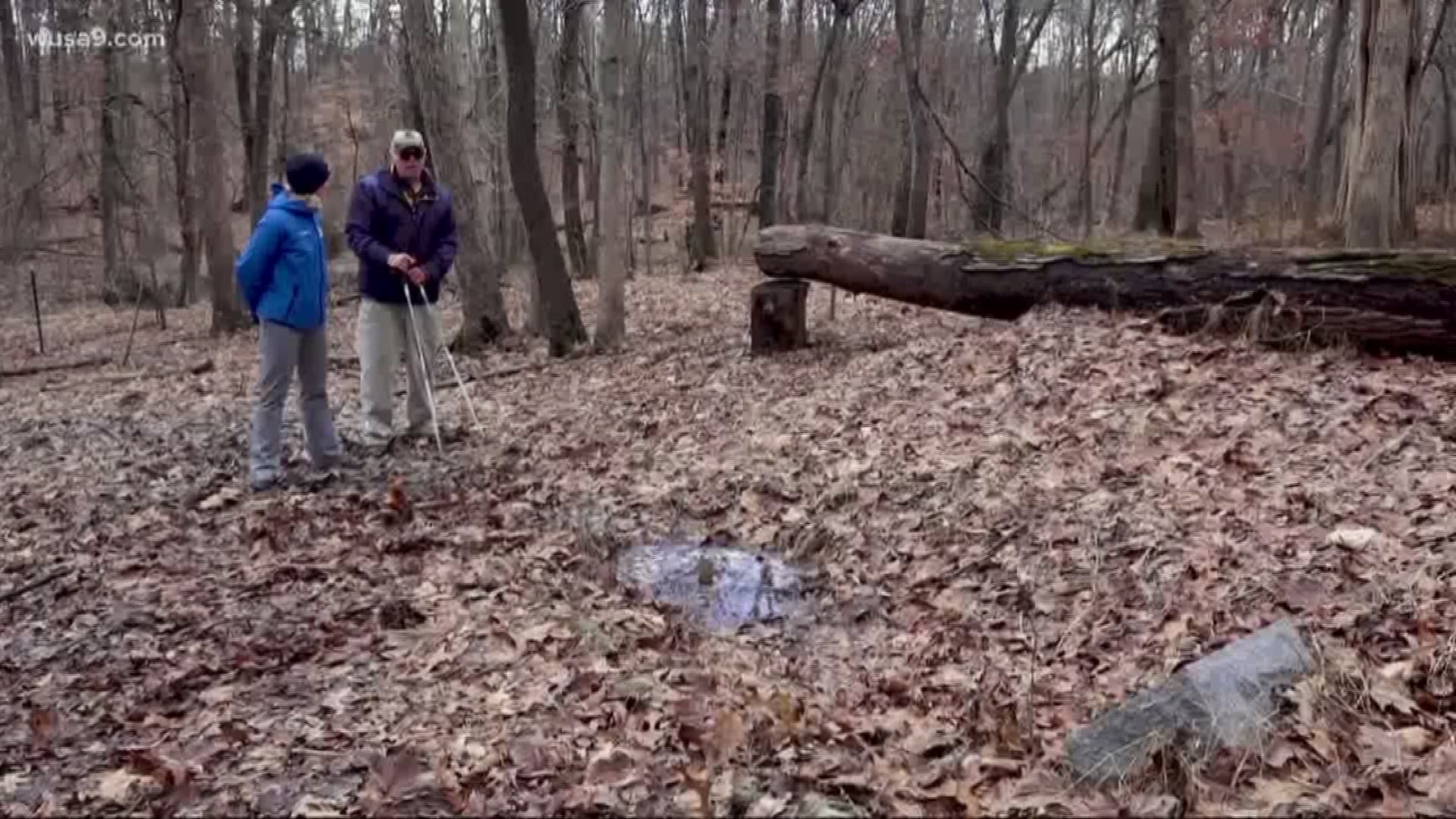

"I would go over there and hike on my lunch hours and wander as I call it. For a year, I wandered all over the place," Koenig said. "I happen to see this headstone. It was tilted, and I thought, 'Why would somebody be buried down here?'"

Koenig said he noticed more than just one headstone.

"Then I started looking around and there's depressions everywhere. I thought, 'What’s going on here? Is this a graveyard?'" Koenig said.

Drawn to the mysterious graveyard, Koenig returned over and over marking every grave with a wooden post and a flag. That was 15 years ago.

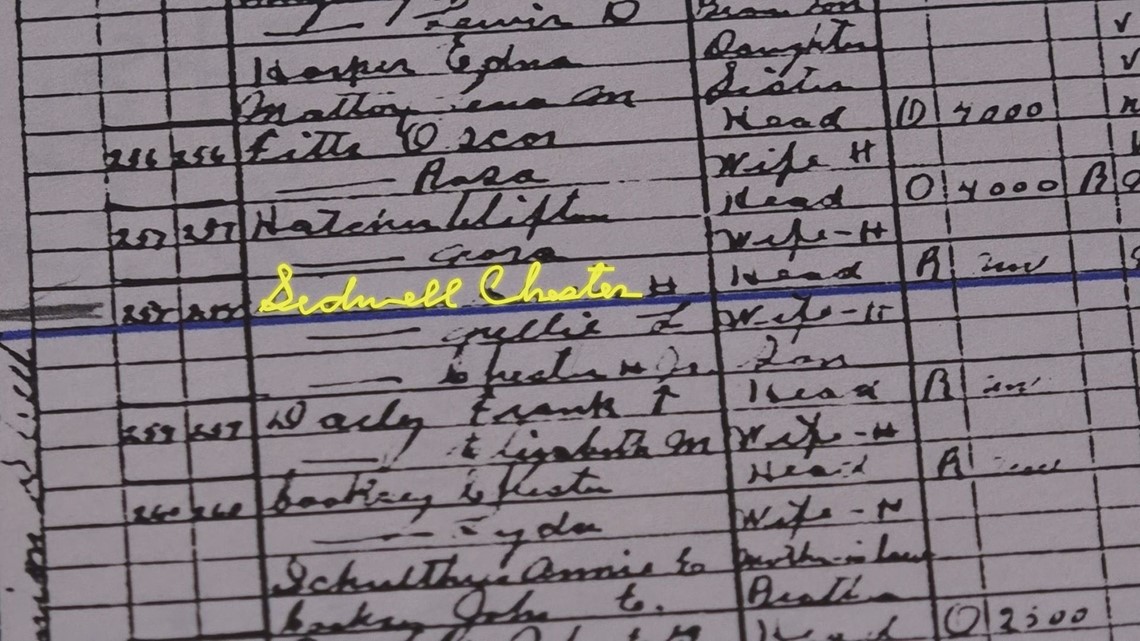

He was intrigued and wanted to know who these people were. Koenig researched the name on the one marked gravestone and learned Chester Sidwell was African-American and that the location was a forgotten African-American cemetery.

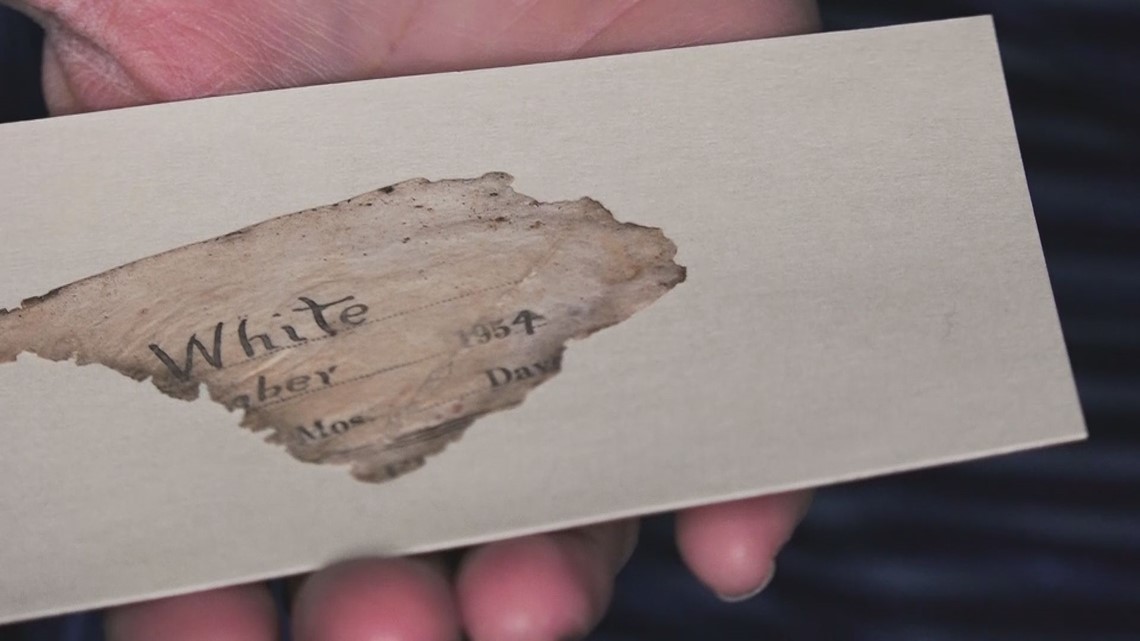

Then, when he began clearing debris from the grave sites, he made another amazing discovery.

He found two tiny rusted metal and glass containers. They were grave site tags left by the funeral home. Inside each of them were tiny pieces of paper revealing two more names.

Using those three names, Koenig poured over census going back as far as 1860 -- the year before the Civil War started.

Even though some of the people buried there were alive in 1860, they weren’t listed in the census, because they were slaves and were considered property, not people.

But Koenig found them in the 1870 census after the Civil War when slaves had gained their freedom.

"It shows their resilience. One day they're a slave. They've emancipated the next day. They really have no training, no education, no nothing, no money no land," Koenig said.

They turn around and literally within 10 years had established a community. They are prospering. Their kids are learning to read.

They acquired land, built houses, and even a school. We're told they were in this field close to this church on Sycolin Road.

The church is the only remaining structure from the community.

"I call them my people. Obviously, they’re not my people," he said.

You might wonder why Koenig, a white guy, is so interested in the African-Americans buried there. He said he feels a connection.

"I know their families intimately. I researched these families. Their births and deaths," Koenig said.

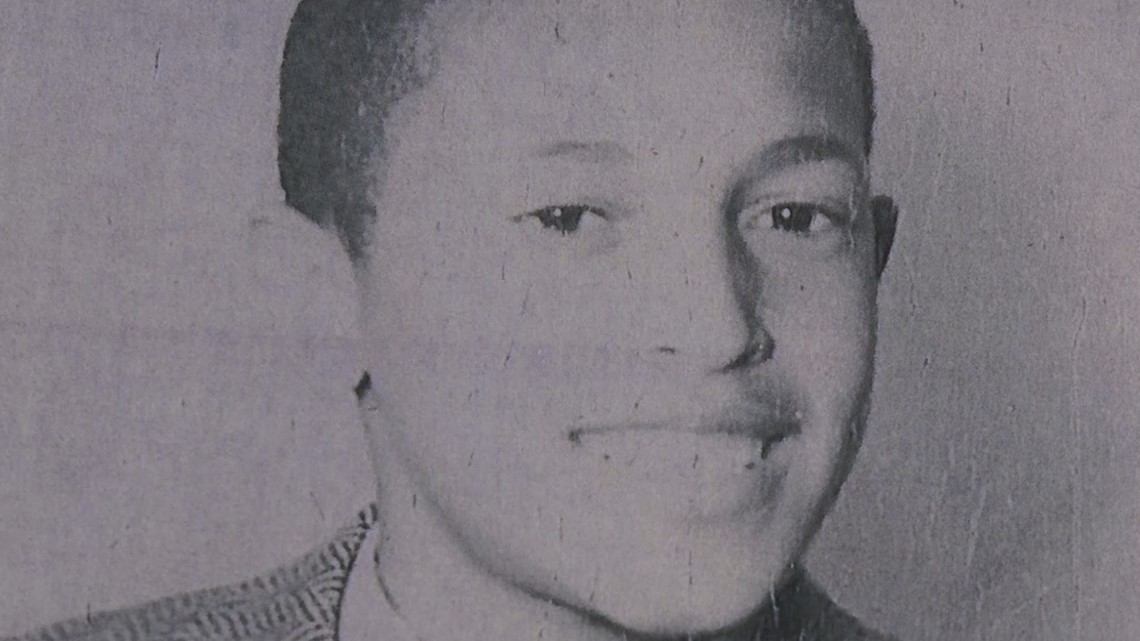

Koenig has identified a family plot where a baby was buried. He found this photo of 13-year-old Paul Franklin Johnson and a eulogy written when he died in 1943.

His son, also named Paul Johnson, is 86 years old and still lives in Leesburg, Va.

"I have a grandmother buried there and a father buried there," Johnson said.

Johnson is concerned about his father’s and grandmother’s final resting place. Koenig identified 42 graves there, but believes there could be many more.

Koenig thinks it is the largest traditional African-American cemetery found undisturbed and intact. His discovery helped stop the town from putting a road through the land.

But the cemetery has not been well maintained. While the town has tried to protect the grave sites with fencing, drainage is a huge problem as water pools in the grave sites.

Pastor Michelle Thomas is the executive director of the Loudoun Freedom Center, a nonprofit that cares for two other African-American cemeteries in the county. She maintains the cemetery is not maintained.

"This is sacred ground. We want to honor our heritage. We want to honor those persons that were a part of our society that contributed so much that didn't have a voice in their lifetime," Thomas said.

For the past four years, Thomas has been trying to get the town of Leesburg to give the cemetery to the Freedom Center so they can take care of it.

No one knows what the property is worth, because the town has not done an appraisal. But it does sit across from the Leesburg Airport and is in the airport's buffer zone, so nothing can be built on it.

In January, Leesburg Mayor Kelly Burke explained the town would not give the land to the Freedom Cemetery because of the connection with the Federal Aviation Administration.

After WUSA9 started asking questions, Leesburg officials finally agreed to give the land to the Freedom Center.

"Four years, four daunting years of a horrible fight. It's overwhelming, but we won. That's the big deal," Thomas said. "Hey, thank you, but thank you camera. I sure appreciate it."

Thomas and Koenig envision a beautiful, sacred place with interpretative signs that tell an American story, a story that’s often been forgotten.

"It's an important statement that every American must understand; that black history is American history, and it requires all our help while and black to save it," she said.

In the next few weeks, the town of Leesburg will carve out the land the grave sites sit on, have it appraised, hold a public hearing, and then transfer the land to Loudoun County Freedom Center.