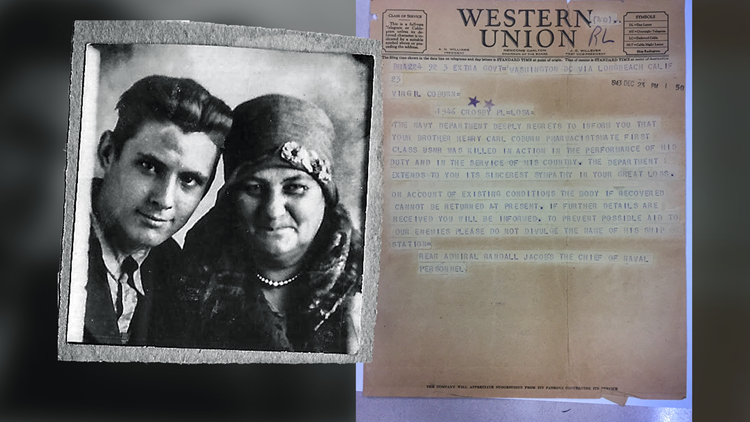

She set aside her iPhone and held the fragile Western Union telegram delivered two days before Christmas, on Dec. 23, 1943.

It was a message from the United States Department of the Navy, crossing the country from Washington. DeWaun Neprud’s great-uncle, Henry Carl Coburn, was killed in action across the Pacific, his body not recovered.

“On account of existing conditions, the body, if recovered, cannot be returned at present,” the telegram read. Adding to the gravity of the situation, “to prevent possible aid to our enemies, please do not divulge the name of his ship or station.”

RELATED: Fallen and Forgotten

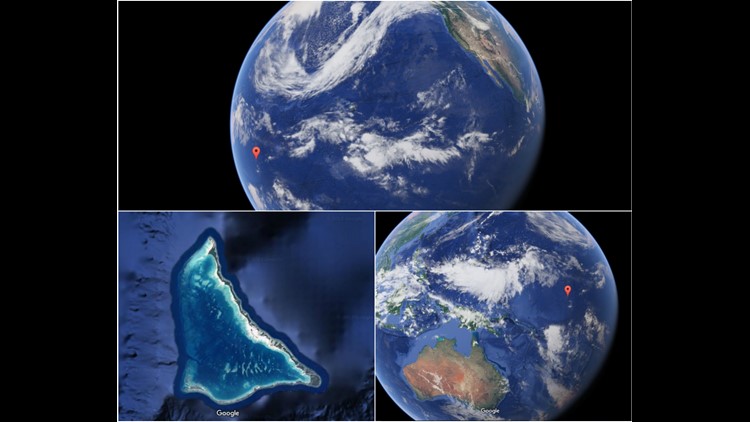

Neprud keeps the brown telegram in a crisp, clear envelope, passed down to her in near mint condition over two generations. Her great-uncle Henry was never found, lost after his boat hit a mine in the coral lagoon within the islands of Tarawa.

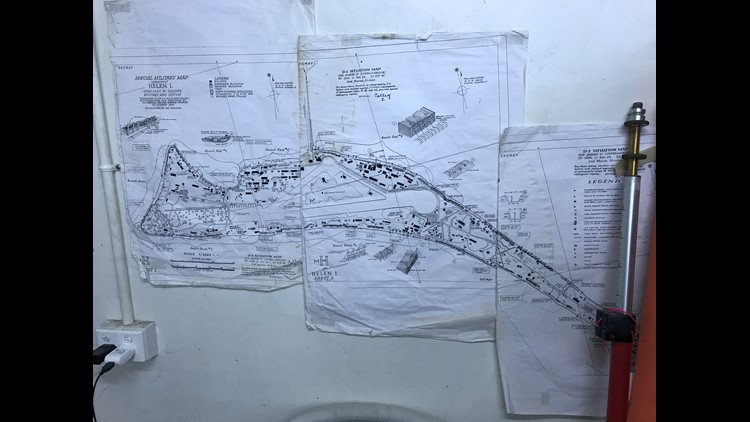

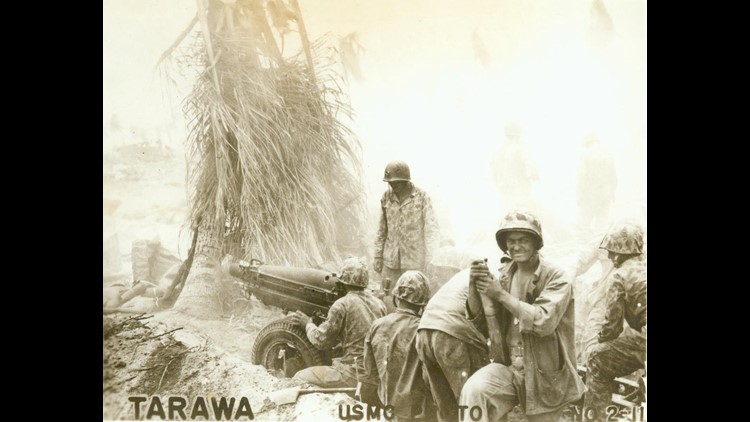

The remote Pacific atoll between Hawaii and Australia was the site of a decisive World War II battle beginning Nov. 20, 1943. A Japanese fortress unleashed a fury of firepower on Tarawa that killed 961 Americans over the course of three days.

The Allied victory left only 17 Japanese survivors, out of a force that started with 3,600 men.

RELATED: 8 facts you didn't know about Tarawa

PHOTOS: Tarawa past and present

But 74 years later, Neprud is still waiting to learn what happened to her great-uncle – if his body was lost in the lagoon, or, like hundreds of other U.S. service members, buried in a lost grave under the sands of Tarawa.

“It is a piece of my history that’s not solved,” Neprud said in an interview Wednesday. “The family never really talked about it too much. I think they just accepted it. I think that generation just accepted that the body wouldn’t be recovered.”

Over the course of a WUSA9 investigation approaching eight months, interviews and records requests show the Pentagon has failed to implement two major recommendations from a top government watchdog – delays that weaken the overarching recovery mission of identifying missing in action Americans.

The U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) released the recommendations in July 2013, as part of a scathing report documenting how two defense agencies mismanaged the recovery of American remains overseas.

Online records show seven of nine proposals from the report were left unimplemented earlier this year. By November 2017, two are still outstanding.

The problems according to GAO boil down to disparate issues:

- Personnel files do not exist for all of America’s missing in action service members.

- Laboratories that analyze artifacts from grave sites operate inefficiently, or duplicate work.

The matter of personnel files tracking all MIA Americans is the most pressing problem, with nearly 73,000 U.S. troops still missing from World War II.

“They do have files for Vietnam MIA cases, but it’s expanding to all of the World War II cases that’s an overwhelming workload for them,” said Brenda Farrell, the author of the 2013 GAO report. “It’s a matter of keeping track of everybody. Being able to share information, being efficient. This is very challenging for them.”

As a result of Farrell’s report, the Defense Department agencies in charge of MIA recoveries merged into a new arm of the Pentagon, known as the Defense POW / MIA Accounting Agency (DPAA).

In a June interview, DPAA Acting Director Col. Fern Sumpter Winbush said a new digital file system is being developed, but the task of confronting the problem is easier said than done.

“The challenge that we have is taking, in many cases, hard files, flat files, pieces of paper, photographs, negatives, microfiche, and getting them into that system,” Sumpter Winbush said.

“And oh, by the way, some of that information, is still classified.”

The second recommendation involves two government laboratories and artifact analysis. In 2013, one lab was operated by the U.S. Air Force, the other operated by DPAA’s now-dissolved predecessor, the Joint Prisoner of War / Missing in Action Accounting Command (JPAC).

Both labs are now absorbed under DPAA, but a plan hasn’t been presented to GAO that sufficiently explains which lab handles which specific cases.

“In several ways, this could impact the families of MIA service members,” Farrell said. “If those two labs aren’t communicating well with each other about the status, then who is passing along the information to the service casualty offices that keep family members apprised of the status of their missing person?”

Farrell also stressed that potential confusion between the lab personnel could slow the MIA identification process.

“It’s, why do you want two labs doing the same thing?” Farrell said. “If they have complimentary roles, then you want to make sure that everybody knows, ‘this is the part that I do, and other times, the other lab does that part.’”

Sumpter Winbush attributed most identification delays to the complex nature of DNA analysis.

“All of the easy cases have been done, we now are left with very challenging remains,” Sumpter Winbush said. “Some of them, even if they’ve been interred in a cemetery, they’ve been treated, that causes issues with being able to extract the DNA.”

Since it was established in January 2015, DPAA has made significant, and quantifiable progress. After the Pentagon identified on average only 72 MIA service members per year, Congress mandated in 2009 that a goal of 200 identifications be met by 2015.

In October 2017, DPAA announced it identified the remains of 201 troops, exceeding the benchmark for the first time. The development was first reported by WUSA9.

However, a closer review reveals not all 201 sets of remains were newly discovered.

In an October records request, a DPAA spokesman said only 183 sets of remains were from previously undiscovered individuals.

As for the other 18 service members – their remains were once mingled and buried together. The government knew who was buried in the grave but didn’t know which skeletal remains belonged to whom.

“I’m disappointed that they didn’t move faster, of course, to meet their goal in 2015,” Farrell said. “But the good news is that they do have a lot underway.”

PHOTOS: Excavating WWII servicemembers on Tarawa

As of October 2017, there are still 452 Americans never been recovered from the Battle of Tarawa. Neprud, the relative of MIA sailor Henry Coburn, has been contacted by a Navy genealogist.

Coburn is still listed as Missing in Action, according to a database assembled with current MIA records.

One of Neprud’s family members submitted DNA to the Defense Department in the summer of 2016.

She has not heard back since.

“I just wish that I had known him. Because obviously, I don’t have any of those memories to share,” Neprud said. “I do have hope actually. I’m very much an optimist. It’ll come, eventually.”